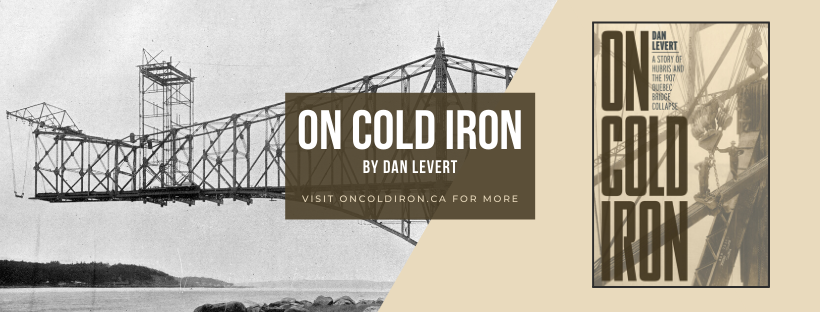

My book, On Cold Iron, A Story of Hubris and the 1907 Quebec Bridge Collapse, tells the story of how Canadian Indigenous people from Kahnawake first became involved in high steel work. It also describes what happened to the children of Kahnawake in the wake of the disaster. In 1907 thirty-three ironworkers from the Mohawk village of Kahnawake were killed when the Quebec Bridge collapsed during construction. The disaster left fifty-two minor Kahnawake children fatherless. The week after the disaster, the Federal Department of Indian Affairs dispatched an experienced agent to meet with the Chief and Council in Kahnawake. The parish priest was in attendance. The agent, James Macrae advised the Council that although the government could not “take in hand the cause of the widows and orphans” to obtain damages, it did offer the department’s assistance in arranging for concerted action. As far as the priest was concerned, the only pressing matter was to relieve the widows by taking their children and placing them in industrial schools. He said there was room at a school in Manitoulin, Ontario. Wikwemikong was a residential school for children run by the Jesuits and funded by the federal government. It was known for its strict discipline. Macrae said he would discuss it with his boss and asked for a list of the children. Fortunately, Macrae and his boss thought ill of the idea and ultimately the children stayed in their community. The tradition of the Mohawk men working on high steel that began in 1886 with the construction of the CPR bridge near Kahnawake continued after the collapse of the bridge and in fact, the young Mohawk men from the community wanted more than ever to work on high steel in rivet gangs. Although the children were not sent away to Residential Schools, they attended one of 11 Day Schools that operated in the village of Kahnawake between 1868 and 1988. These schools were run by churches and funded, managed and controlled by the Federal Government. Abuse, physical and sexual, was common in these schools. As one elder said, the only difference between Day Schools and the Residential Schools was that you got to go home at night. A class action was brought in 2018 on behalf of the victims of all Day Schools across Canada. The Federal Court certified a nation-wide settlement in 2019, which has resulted in compensation being paid to many who suffered. Claims can be made until July 2022. Muskrat Falls and the Quebec Bridge |

Dan Levert's BlogProfessional engineer, construction lawyer and author of On Cold Iron. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed